Biography

I teach and write about texts from the late Middle Ages and theoretical and methodological questions in present-day literary studies. I am co-editor, with James Simpson, of the Norton Anthology of English Literature, Eleventh Edition, Vol. A, The Middle Ages (2024). In January 2025, I begin as Book-Review Editor at the journal Exemplaria: Medieval, Early Modern, Theory, in which role I commission book-review essays. (Please reach out to pitch ideas!) Most recently I guest-edited the essay cluster “Grounds for a Trans-Regional Medieval Studies, Beyond the Global” for postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies. My editorial introduction is freely accessible here.

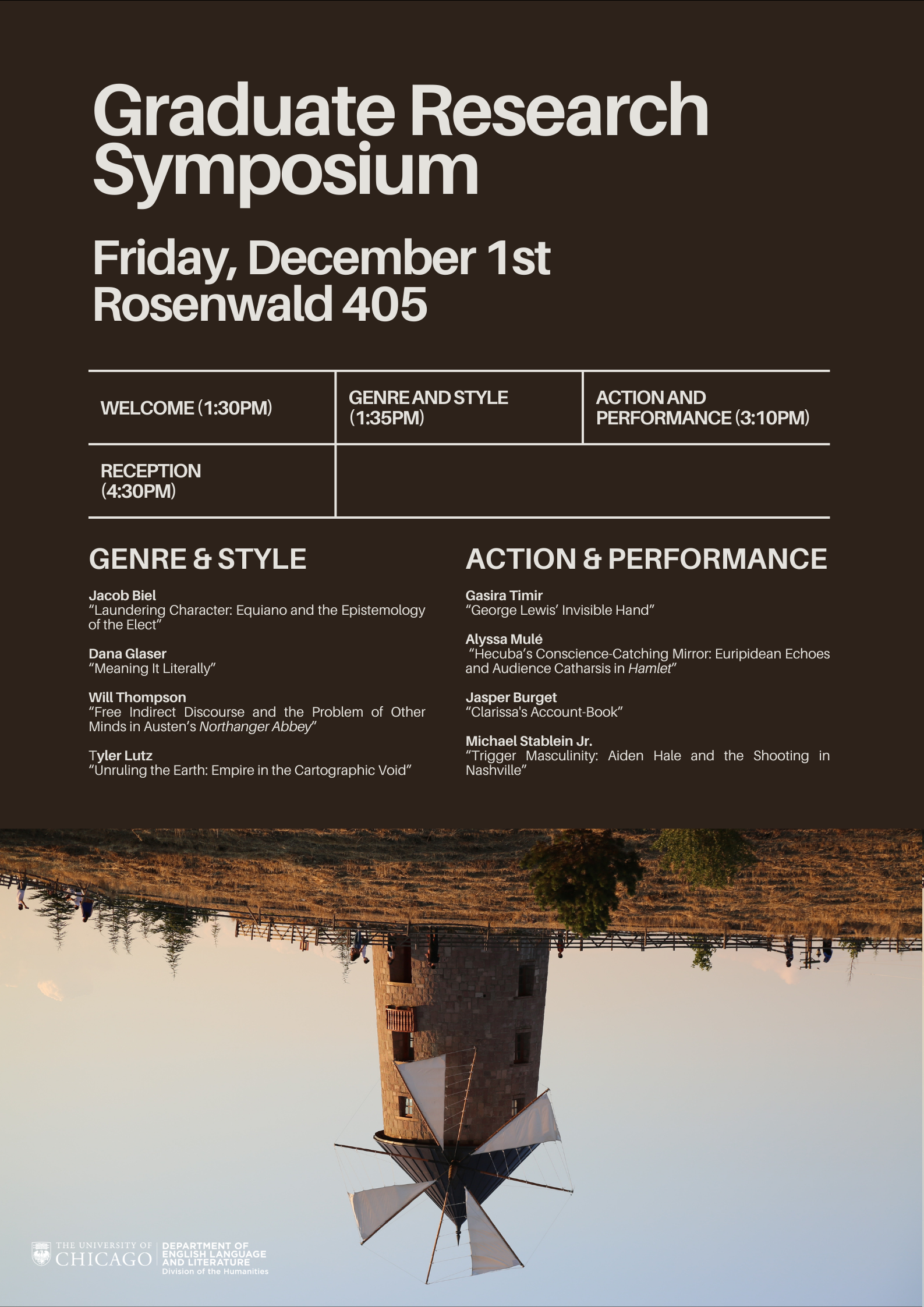

Photo Credit- Erielle Bakkum

Select Publications

- Symptomatic Subjects: Bodies, Medicine, and Causation in the Literature of Late Medieval England (Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2019)

- “The ‘Physician’s Tale’ and Chaucer’s Art of Prosopopoeia,” in Literary Forms and Cultural Power in Medieval and Early Modern Literature: A Book for James Simpson (2024), ed. Nicholas Watson, Sebastian Sobecki, and Daniel Donoghue

- “What Is ‘Postmedieval’?: Embedded Reflections,” in boundary 2 50:3 (2023)

- “Fiction and Belief: Approaching Medieval Latin Christendom,” in The Routledge Handbook on Fiction and Belief (2023), ed. Alison James, Françoise Lavocat, and Akihiro Kubo

- “Literary Persons and Medieval Fiction in Bernard of Clairvaux’s Sermons on the Song of Songs,” in Representations 153 (2021)

- “Who Has Fiction? Modernity, Fictionality, and the Middle Ages,” in New Literary History 50.2 (2019)

- “Langland’s Poetics of Animation: Body, Soul, Personification,” in the Yearbook of Langland Studies 33 (2019)

- “Prosopopoeial Heaviness in Chaucer’s Book of the Duchess,” in Chaucer and the Subversion of Form (2018), ed. Thomas A. Prendergast and Jessica Rosenfeld

- “Medieval Literary Theory,” in the Literary Encyclopedia, vol. 1.2, English Writing and Culture: Medieval and Early Modern England, 1066-1485

- “Modernity within the Middle Ages,” review essay in the Journal of English and Germanic Philology 116.3 (2017)

- “Philology and the Turn Away from the Linguistic Turn,” in Florilegium 32 (2017 for 2015)

- “Literary Genre, Medieval Studies, and the Prosthesis of Disability,” in Textual Practice 30.7 (2016)

- “Scales of Reading,” in Exemplaria 26.2-3 (2014), special issue on “Surface, Symptom, and the State of Critique”

- “Genre,” in A Handbook of Middle English Studies (2013), ed. Marion Turner, Wiley-Blackwell Critical Theory Handbooks